Myeloma Genomics and Microenvironment and immune profiling

Category: Myeloma Genomics and Microenvironment and immune profiling

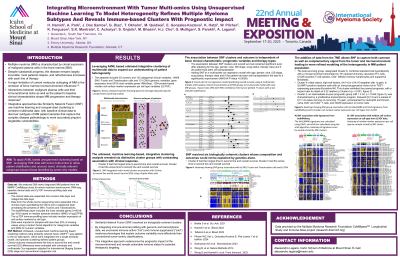

Integrating Microenvironment with Tumor Multi-Omic using Unsupervised Machine Learning to Model Heterogeneity Refines Multiple Myeloma Subtypes and Reveals Immune-Based Clusters with Prognostic Impact

(PA-234) Integrating Microenvironment with Tumor Multi-Omic using Unsupervised Machine Learning to Model Heterogeneity Refines Multiple Myeloma Subtypes and Reveals Immune-Based Clusters with Prognostic Impact

Habib Hamidi, PhD

Distinguished Scientist

Genentech

A major limitation of current molecular subtyping of Multiple Myeloma (MM) is the omission of bone marrow microenvironment influences. Interactions between malignant plasma cells and their immune/stromal niche critically shape MM progression and therapy response. We hypothesized that integrating TME data with tumor multi-omics would refine patient stratification and uncover novel, clinically relevant subgroups beyond those identified by tumor-only models.

Methods: We analyzed 389 newly diagnosed MM patients from the MMRF CoMMpass study for whom matched whole-exome, RNA-seq, baseline clinical data and CyTOF immune-profiling data was available. Using an unbiased, unsupervised machnile learning based clustering method based on similarity network fusion (SNF) the different modalities were integrated into a single similarity model, and spectral clustering defined patient groups. The resulting clusters were compared with the twelve tumor-only MM-PSN subgroups from our previous work (Bhalla et al., Sci Adv 2021). Clinical outcome measurements like time to second line and overall survival (OS) differences were evaluated with multivariate Cox regression adjusted for International Staging System (ISS) stage and conventional cytogenetic risk.

Results: SNF resolved six biologically coherent clusters whose composition and outcomes could not be explained by genetics alone. The best-surviving group, designated Cluster 6, combined standard-risk hyperdiploidy with a microenvironment dominated by Th1-skewed immunity: abundant Th1 cells, CXCR3-positive T-cell subsets, CD4⁺ effector-memory lymphocytes and supportive fibroblasts. At the opposite extreme, Cluster 4 united classic high-risk lesions, t(4;14) or t(14;16) together with 1q gain, in SLAMF7-positive myeloma cells with an immunosuppressive niche rich in TIGIT-expressing granzyme-B-positive NK. This cluster exhibited the poorest prognosis, with a hazard ratio for death of 4.46 relative to Cluster 6 (p < 0.001). Cluster 2, an intermediate-to-poor prognostic group (HR = 2.14, p = 0.07), was characterized by a proliferative transcriptomic program, frequent t(4;14) and a subset of t(11;14) cases carrying co-occurring 11q gain, accompanied by neutrophil enrichment, naïve CD8⁺ and CD4⁺ T cells, and CD28 expression on tumor cells. In multivariate analysis cluster membership remained an independent predictor of OS after adjustment for ISS and cytogenetics, outperforming individual high-risk genomic markers.

Conclusions:

By integrating immune-stromal profiling with genomic and transcriptomic data, we uncovered immune-active (“hot”) and immune-suppressed (“cold”) myeloma phenotypes that explain outcome variability more effectively than conventional tumor-centric classifications. This integrative approach underscores the prognostic impact of the microenvironment and reveals actionable immune states for potential therapeutic targeting.